The more I’ve been writing about bookmakers the more I’ve come to realise that some of them have a genuinely fascinating history. There is Ladbrokes, for example, which started off life as a commission agents for horses that had been trained at Ladbroke Hall, a country estate in Warwickshire. Or Coral, which was started as an on-course bookmaker by Joe Coral in 1926 who expanded his enterprise by running speedway meetings with a friend at Harringay before opening a credit office in London’s West End. Even BetVictor’s history is more interesting than you might expect at first, having been started by William Chandler fifteen years after he’d opened Walthamstow Stadium and remained in the family until it was taken over by Michael Tabor in 2014.

The more I’ve been writing about bookmakers the more I’ve come to realise that some of them have a genuinely fascinating history. There is Ladbrokes, for example, which started off life as a commission agents for horses that had been trained at Ladbroke Hall, a country estate in Warwickshire. Or Coral, which was started as an on-course bookmaker by Joe Coral in 1926 who expanded his enterprise by running speedway meetings with a friend at Harringay before opening a credit office in London’s West End. Even BetVictor’s history is more interesting than you might expect at first, having been started by William Chandler fifteen years after he’d opened Walthamstow Stadium and remained in the family until it was taken over by Michael Tabor in 2014.

Yet of all of the various companies that exist nowadays none of them have a history as fascinating and thrilling as that of the Tote. From being formed as a government-run company by Winston Churchill in between the two world wars as a way of allowing the government to get hold of some of the gambling revenues and re-investing it back into the sport through to being privatised and eventually bought by Betfred, the Tote essentially tells the story of British bookmaking from its more formative years through until now. On this page I’ll have a look at why it came it about in the first place, how it developed over the years and where it looks likely to go in the future. This will be no means be a definitive history, but hopefully it will cover most of the big moments in the history of one of bettings biggest and best-known companies.

In the Beginning

In many senses, there’s no way that people placing bets could have taken the government by surprise. Yet, back in the early part of the 20th century, the main way that people could place a bet was via a bookmaker based on a racecourse or an illegal off-course bookie. The later was something that the government strongly disapproved of – hence the ‘illegal’ part – but it happened anyway. It was felt by the powers that be that something should be done in order to stop these illegal bookmakers benefitting from the sport of horse racing and taking it away from the industry. That ‘something’ turned out to be the Racecourse Betting Act, which was passed in 1928 and resulted in the setting-up of The Racehorse Betting Control Board.

As part of the Act, this government-appointed board was created to provide that alternative to the illegal bookies. This alternative was, as you would expect, state-controlled and much safer than going to some dodgy bloke in a back street and hoping he wouldn’t just take your money and disappear. This new company was a statutory corporation and the aim of it was to funnel money back into horse racing, rather than simply taking it away for the government’s coffers. Thought the Act was passed in 1928, Tote betting wouldn’t take place for the first time until the 2nd of July of the following year, when punters at flat races at both Newmarket and Carlisle got to do so for the first time. In 1930, Tote Investors Limited was set up by ‘a group of gentlemen interested in the welfare of racing’, channeling both credit bets and off-course bets into the Tote pools. Though a separate entity, it was bought by the Tote in 1962.

What Is the Tote?

Totepool Betting Explained by Betfred

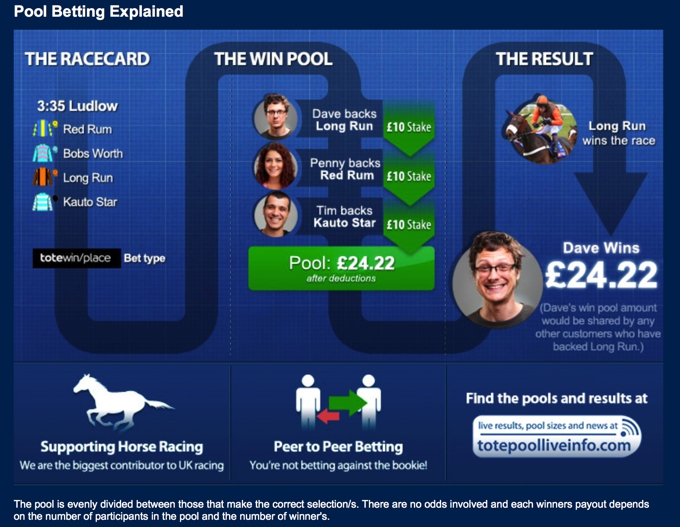

This seems like an appropriate time to give a quick mention to what exactly Tote betting entails. After all, if you think it’s just like any other bookmaker then you might be wondering what all the fuss is about and why it matters. Tote betting is essentially another term for parimutuel betting, which is a system whereby all bets that are of a certain type get put into a ‘pool’ and winners receive a payout depending on the number of entrants and the size of their stake. Unlike fixed-betting odds that are determined according to the bookmaker’s decision to offer whatever they fancy, Tote odds are decided upon by the number of bettors and the amount wagered.

Traditional bookmakers make their money by giving themselves an ‘edge’ with the odds that they offer to their customers, but that’s not how it works with the Tote. Instead, the house has a take or ‘vigorish’ (often referred to as ‘the vig’ from the overall pool that they remove before paying out. That means that any odds offered have been calculated after a percentage of the pool has been removed from the overall pot of money. As far as the type of bets you can place are concerned, the Totes offer things in a slightly different way. You can still place a Single Win or an Each-Way bet, but you can also opt for a Place bet as well as the likes of Tote Quadpot bets or the most famous, the Tote Scoop6.

The First Big Change

Heading back to the history of the Tote now, the first big change to proceedings came in 1961 with the introduction of the Betting Levy Act. This was the moment that the Racehorse Betting Control Board was renamed as the Horserace Totalisator Board and the slang term ‘the Tote’ was first used. It was also known as ‘the Nanny’ in cockney rhyming slag, based on the idea of the nanny goat rhyming with the Tote. Far more important that the company’s new name was the fact that this new Act completely changed the way betting worked, with the legalisation of betting shops on the streets of Britain. Whilst other bookies were allowed to offer odds on things other that the horses, the Tote is only allowed to open shops that offer odds on horse racing bets and they have to be at Tote prices.

Heading back to the history of the Tote now, the first big change to proceedings came in 1961 with the introduction of the Betting Levy Act. This was the moment that the Racehorse Betting Control Board was renamed as the Horserace Totalisator Board and the slang term ‘the Tote’ was first used. It was also known as ‘the Nanny’ in cockney rhyming slag, based on the idea of the nanny goat rhyming with the Tote. Far more important that the company’s new name was the fact that this new Act completely changed the way betting worked, with the legalisation of betting shops on the streets of Britain. Whilst other bookies were allowed to offer odds on things other that the horses, the Tote is only allowed to open shops that offer odds on horse racing bets and they have to be at Tote prices.

Also formed as part of the 1961 Act was the Horserace Betting Levy Board, which was a statutory non-departmental public body. Its job was, and remains, to collect a statutory levy from the Tote and then re-distribute that appropriately throughout the horse racing industry. Its proviso changed slightly with the introduction of the Betting, Gaming and Lotteries Act of 1963 and it continues to operate in accordance with the rules and regulations introduced back then to this day. As far as the restrictions put in place on the Tote regarding betting shops were concerned, they remained in place until 1972 and in 1973 a new bookmaker was launched called Tote.

How the Tote Developed

After the lifting of the restrictions in 1972, the Tote continued to developed at a decent rate, pretty much in-line with most other bookmakers of the period. In fact, Tote betting was so popular that other bookies began to want in on the action, frustrated by the fact that the Horserace Totalisator Board was the only company that was allowed to take pool-style bets. As a consequence Tote Direct was launched in 1992 and that allowed mainstream bookmakers to take bets that were then added to the Tote pot. Tote Direct channeled these new bets into the Tote pool and ensured that bookies followed the rules of the game as set out by the various government Acts. It was a moment that opened up what was a restrictive way of betting to the wider industry and also ensured a bigger take for the Tote itself.

In 1993, rules changed once more in order to allow betting shops to be open in the evening, whilst in 1999 something happened that saw the Tote make a move into the mainstream betting market. That ‘something’ was a link up with Channel 4 Racing and the introduction of the Scoop6 prize I mentioned earlier. Back then that prize involved punters attempting to select the winners of six different televised races, which was a tricky task that brought with it higher odds. In fact, the odds were so high that the Scoop6 prize produced the first millionaire ever to come from horse race betting.

There were more governmental shifts around the Tote in 2001 when a decision was taken to remove the responsibility for making Horserace Totalisator Board appointments away from the Home Secretary and move it to the Department of Culture, Media and Sport. Three years later and another Act of Parliament sees more shifts in how bookmakers are allowed to operate. Prior to the introduction of the The Gambling Act of 2004 bookmakers remained closed on Christmas Day and Good Friday. This new Act removed the Good Friday restriction, however, meaning that the 25th of December was then the only day on which gambling could not officially take place. The Tote, of course, followed suit with the rest of the companies and began to offer odds on Good Friday racing.

The Tote’s popularity continued to grow, no doubt in no small part because the company was able to operate in pretty much the same way as all other well-known and much loved bookmakers. In fact, the popularity of the Scoop6 bet as such that on the 22nd of November in 2008 a record breaking amount of money was entered into the Tote’s Scoop6 betting pool. More than £4 million was bet on one day of racing, with eight winners picking up £437,011.39 each. Any lingering doubt that remained over whether or not the Tote and its different way of betting had been truly embraced by the horse race betting public was erased once and for all.

Privatisation of the Tote

Though it was clear that the public had well and truly adopted the Tote as a unique and interested way to bet by the time 2008 came around, talks of privatising it had been going on since well before then. In fact, a study into the possibility of selling it off was carried out by Lloyds Bank as early as 1989, with the Conservative government of the time giving it serious consideration. The horse racing industry wasn’t happy with the suggestion, however, and strongly opposed any such move. Though talks continued for another six years, any possible privatisation was abandoned by Michael Howard when he became Home Secretary in 1995. Everything changed again two years later, however, when Labour came to power in a landslide election and Jack Straw became the new Home Secretary.

Though it was clear that the public had well and truly adopted the Tote as a unique and interested way to bet by the time 2008 came around, talks of privatising it had been going on since well before then. In fact, a study into the possibility of selling it off was carried out by Lloyds Bank as early as 1989, with the Conservative government of the time giving it serious consideration. The horse racing industry wasn’t happy with the suggestion, however, and strongly opposed any such move. Though talks continued for another six years, any possible privatisation was abandoned by Michael Howard when he became Home Secretary in 1995. Everything changed again two years later, however, when Labour came to power in a landslide election and Jack Straw became the new Home Secretary.

Mr. Straw decided to launch a new study into the possibility of privatising the Tote and the company’s fate was as good as sealed when Labour made its privatisation a commitment in its 2001 election manifesto. Of course things were never going to be easy when it came to selling the Tote off to a private company, not least of all because it was a statutory corporation, stopping a sale from taking place. That’s why the Horserace Betting and Olympic Lottery Act was introduced in 2004, converting it to a limited company and ensuring that a sale was now possible. The next trick was to find a buyer, with plenty of companies feeling that it would be a decent addition to their portfolio.

In his 2006 Budget the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, announced that the company would definitely be privatised. Initially the government invited Tote staff and a consortium of racing people to make a formal bid for the Tote, which would need to be in by the 26th of January 2007. Their bid was indeed entered successfully, but the Department for Culture, Media and Sport rejected it on account of the fact that it was backed by private equity. By March of the following year it was clear that the government’s chosen bidders wouldn’t be able to get a satisfactory bid in and so it was confirmed that the Tote would be sold on the open market. A slight spanner was thrown into the works when an extensive audit revealed financial information that forced the government to keep things as they were.

Tony Blair stood down as Prime Minister in 2007, with Gordon Brown taking over as the leader of the Labour Party and, therefore, the country. In 2009 he confirmed that the Tote would be sold alongside a number of other assets that were publicly owned, but with a general election looming in 2010 nothing was actually done about it. Labour lost that election, with the Liberal Democrats entering into a Coalition Government with the Conservative Party. This new government began the bidding process on the Tote, with as many as eighteen different bidders getting involved at the first round of bids.

It was the 31st of January 2011 when the government confirmed that it had drawn up a shortlist of prospective buyers for the Tote, though it declined to confirm who they were actually from. Just because the government didn’t confirm who’d made the bids didn’t mean that the press didn’t speculate, of course, with the rumours suggesting that there were eight bids in the running. These were believed to be from Betfred, billionaires David and Simon Reuben, the relatively newly formed super-bookie of Gala Coral Group, a conglomerate of business people led by Sir Martin Broughton and known as Sports Investment Partners and a foundation set up by the Tote’s then management. It was also rumoured that a sixth bid might have been added to the shortlist led by Stan James, though this was never confirmed.

In the end the government narrowed the field to just two bidders: Betfred and Sports Investment Partners. The rumours were that government ministers were leaning towards Betfred as the Manchester-based company had offered the most money to take over the Tote and its associated betting shops, leading to the horse racing industry to make clear who it would have preferred to win. Sir Martin Broughton was a ‘known entity’ to the industry because he regularly attended races and was himself a race horse owner. Industry leaders, meanwhile, wrote to the government and declared that “With Betfred, racing would be forced to negotiate with a private company provided with a monopoly on pool betting on racing’s product”.

The government wasn’t keen to be held to account by the racing industry, though numerous backbench Tory MPs had constituencies that included both stables and racecourses. In a bid to relieve the fears of the industry the government declared that 50% of the sale’s net proceeds would go directly to the industry and that the bid would be awarded to the company that they felt showed the best long-term commitment to the future of racing. The Tote was contributing around eleven million pounds per year to racing at the time, with fears from industry’s leading lights being that Betfred was only really interested in the 517 betting shops that were part of what they were bidding for, hoping that it would help them climb the ladder from the fourth-biggest bookmaker in the country to one of the largest.

In the end the racing industry’s complaints fell on deaf ears, with Jeremy Hunt, then the government’s Culture Secretary, confirming that he’d chosen Betfred’s bid as the winner. It’s believed that the winning bid was worth around £265 million, though this was never confirmed. The sale went through on the thirteenth of July 2011 and the long-mooted privatisation of the Tote was complete, with Betfred being the new owners.

Betfred and the Tote

Did the racing industry’s fears prove unfounded, then, or were the right to be worried about how Betfred would deal with this most important arm of horse racing? To begin with things were certainly considered to be positive. Befred continued to develop the Tote and the online operation, ToteSport.com. In 2015 they completely revamped both the website and the mobile app, making it even easier for punters to have a flutter via this unique betting method. The company also made a £155 million commitment to racing, guaranteeing £11 million for the first year and then £9 million per year for the six years that followed. In actual fact, the company gave more than £12 million per year back to the sport.

Did the racing industry’s fears prove unfounded, then, or were the right to be worried about how Betfred would deal with this most important arm of horse racing? To begin with things were certainly considered to be positive. Befred continued to develop the Tote and the online operation, ToteSport.com. In 2015 they completely revamped both the website and the mobile app, making it even easier for punters to have a flutter via this unique betting method. The company also made a £155 million commitment to racing, guaranteeing £11 million for the first year and then £9 million per year for the six years that followed. In actual fact, the company gave more than £12 million per year back to the sport.

The problem was that Betfred’s exclusive license only ran for seven years from the moment they bought the Tote, meaning that other companies could set up their own pools-style of betting from 2018 onwards. As a consequence the relationship between Betfred and the horse racing industry began to sour in 2017, with Fred Done ordering the closure of forty-nine of the fifty-one on-course shops the company had by July of 2018. The only courses that Betfred would keep a relationship with were Ascot and Chelmsford, which the company owns.

The closure would result in a £6 million loss for the racing industry, with Fred Done declaring that the industry and his company would ‘have to learn to live without each other’. As well as closing the shops, Betfred will also stop sponsoring all races, which is where the biggest financial blow to the industry will come in to play. Prior to Done’s decision to play hardball with the racing industry his company sponsored around one in ten of the ten thousand-plus contests held during the racing year. Given the likelihood of Betfred abandoning racecourses, then, what does the future of the Tote look like?

The Future of the Tote

The horse racing industry’s alliance with the Tote has been fractious ever since the government decided to declare Betfred as the winning bid, with many horse racing stakeholders believing that the Tories had handed the company a ‘cheap pass’ towards granting itself a monopoly of trackside racing pools. Indeed, from 2016 the racing industry has been plotting to start up a rival pools betting service to the Tote. The idea has long been pushed by both the Jockey Club and the Racehorse Media Group, the latter of which is responsible for the media rights of numerous racecourses throughout Great Britain.

The horse racing industry’s alliance with the Tote has been fractious ever since the government decided to declare Betfred as the winning bid, with many horse racing stakeholders believing that the Tories had handed the company a ‘cheap pass’ towards granting itself a monopoly of trackside racing pools. Indeed, from 2016 the racing industry has been plotting to start up a rival pools betting service to the Tote. The idea has long been pushed by both the Jockey Club and the Racehorse Media Group, the latter of which is responsible for the media rights of numerous racecourses throughout Great Britain.

Given that prominent members of the racing industry made efforts to by the Tote when it was put up for sale in 2011 it’s no major shock to see them hoping to do things ‘the right way’ once pools betting is no longer strictly limited to Betfred. Indeed, a Racehorse Media Group spokesperson declared that it could help to improve the Tote’s prospects, saying, “We think that a racing-owned Tote would return more money to racing as well as revitalise a product which is looking rather old and tired now”. With punters staking an average of £5 million per week on the Tote it’s certainly true that there’s a ready and willing audience. Tote betting has long been seen as the ‘sleeping giant’ of the horse racing industry, with many believing that a well run alternative would be popular with the race going public.

Certainly that’s what industry experts believe, with the chairman of the racecourse project steering board, Neil Goulden, saying in June of 2017 that, “…we intend to offer an excellent pool betting service that we are confident customers will prefer, while returning to British racing all monies it raises”. At that point fifty-four of the fifty-nine UK race courses had committed to the racecourse project. That included all of those run by the Jockey Club, Scottish Racing and Arena Racing Company, plus Newbury, York and Goodwood. Chester and Bangor declined to get on board because they run their own in-house alternatives, whilst Ascot is setting up AscotBet and Chelmsford City is owned by Betfred and therefore unlikely to sign up to the alternative to the official Tote.

Does that mean that the Tote, the company that dates back to 1928 and owes its existence, at least in part, to Winston Churchill, is coming to a sad and untimely end? It’s difficult to know for sure, though if the majority of the racing industry sees an alternative manner of pools betting as the future then it’s tricky to see how the Tote will survive for much longer. One thing I can say is that pools betting remains a popular alternative to fixed-odds betting and that is unlikely to change. The official Tote company may not have much longer left, but the general idea of pari-mutuel betting will, if anything, grow stronger as it heads in a different direction dictated by the racing industry itself for the first time in its history.